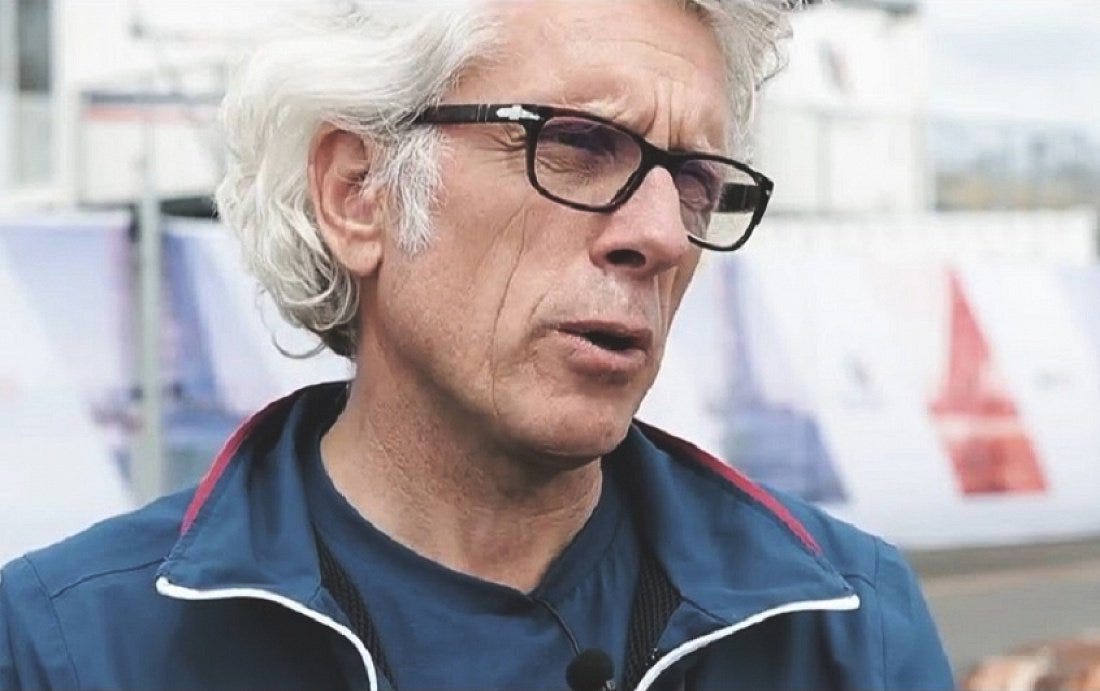

Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula 1 Team chief technical officer James Allison shares his thoughts on challenging for the America’s Cup with Ineos Britannia

The renowned British designer brings a wealth of experience in high-performance sport, having played a key role in the creation of 13 Formula 1 Constructors’ Championship winning cars.

Prior to this week’s partnership announcement from Ineos Britannia and the Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula 1 Team, America’s Cup fans could have been forgiven for not knowing the name James Allison.

However, the British designer’s skills and expertise have earned him legend status in Formula 1, and now he is set to make his mark on the America’s Cup world as his chief technical officer role at the all-conquering Formula 1 team expands to include the Ineos Britannia AC37 challenge.

Allison – who has described the opportunity to be involved in the British America’s Cup campaign as ‘mouth-watering’ – sat down with a small group of motorsports and sailing journalists earlier this week to talk about what lies ahead.

Here are the highlights of the Q&A:

Can you give an indication of where you think F1 expertise is particularly applicable to the challenge of building a boat fast enough to win the America’s Cup?

First off, I think it is worth pointing out that the engineers in America’s Cup – the people who have made that their lives – are very fine engineers and they are working on impressive stuff.

Traditionally they work in a championship that grows up to a crescendo - has its fight on the water and then sort of subsides. So they have this different business model to Formula 1 which this ongoing churn.

The fine detail of the hydrodynamics and the aerodynamics - the numerical optimisation that goes on - this stuff is very impressive. We can hold our end up – but we don’t necessarily transform their world.

But we have definitely got capable engineers who can join that party on an equal footing and hopefully help swell the numbers.

Probably, areas that are harder for America’s Cup teams to do – but are the meat and drink of an F1 team – are:

all the systems that we have in place to know [things like] if you put a hydraulic pipe down a certain length of something, how far away do have to keep all the other things away so they don’t fret on the pipe, and how often down the pipe do you have to support it so that it doesn’t bounce around too much

the type of equipment that we have to inspect stuff, so that we know what we designed is what we built and what we are assembling

all of the design standards that have been painfully learnt and written into procedure for the F1 team, which can then be picked up and used by the community of engineers that is Ineos Britannia

That sort of stuff is pretty valuable. If you want all your good hydrodynamic and aerodynamic ideas to come true – things that are coming from the experienced marine folk on the team, backed up by the capable bodies that are working with them – then the boat has to actually be assembled on time, to the right quality, not break down on the water so the sailors can learn when they are sailing it.

I think that the maturity of the Mercedes Formula 1 team provides a really functional environment for the design engineers then to create designs that ought to be reliable and work. Then hopefully we build in enough raw performance to make that a competitive boat – as well as a reliable boat.

Which people and in which roles at the F1 team do you envisage working on the America’s Cup project?

The truth is that the challenge of the boat will eventually touch on the skill set of most of the people on the engineering and manufacturing side in this team. That’s because if you were to go and dig through the boat you would see that there are things in it that would interest a cooling engineer, a hydraulics engineer, a structural engineer, a composites engineer, a mechanical mechanisms guy, an aerodynamicist, a hydrodynamicist, and so on.

You just name it – the full gamut: electronics, data acquisition, the sensors, pretty much everything that makes up the backbone of an F1 team you could find some part of an America’s Cup boat that they could work on and be excited by. Because the product is really interesting.

So, the type of people that we hope to bring to the party on this project will cover all the technical areas in our team – but not necessarily all at the same time. [For example] we are not making hardware at the moment. The Cup isn’t for a while, so the people who will be making bits will be making prototypey stuff a little bit down-stream from here, and test rigs and the like, and then move on to making boat stuff later on.

At the moment, the type of people from our world - the F1 world - that are involved are some aerodynamicist-type guys, performance simulation-type guys, softwarey-type guys, – and planners.

I doubt when people think about our car roaring around the track, or the boat steaming up and down those courses, whether people give much thought to the planners. But actually, at the beginning of a campaign, they are your most precious asset.

If it’s anything - and this is very similar to F1 - this Challenge is a race against the clock. It’s going to be some years before we actually fight, and it might feel like that’s ages but actually when you look at all the work that is piled up in front of us, it feels like it’s tomorrow.

[That’s why] having the planners who can show you what the critical path is, so that you can then deploy material and folk in that direction, that’s really key, and at the moment we have some F1 planner guys working on that. It’s the least glamorous of tasks – but a really, really, important task.

When Ben Ainslie talks about the Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula 1 Team he uses the word ‘discipline’ a lot. Does that resonate with you as someone who knows the organisation’s culture well?

It’s an interesting word, because if you had asked me to pick adjectives out to describe what it feels like to be a member of this team, discipline wouldn’t be one of the ones I would reach for.

That isn’t to say that there isn’t discipline but it’s not like I one of our goals is to create a disciplined environment.

To me working here is fun, exciting, friendly, kind – this is a very kind team – and enjoyable. Yeah, we set ourselves difficult tasks, and we want to get those tasks done, but there’s an awful lot of laughter too.

I think what Ben means is that if you walk into our design office in any given weekday there’s not just a riotous noise, it’s sort of quiet and focused. There’s hubbub of conversation here and there and there’s laughter, but if you look around on every screen you will see a part of an engineering design with some designer working on it. And people bent to the task of trying to get what we are trying to do as a shared goal.

I think when you walk into a drawing office as large as ours you can’t walk away without a sense of “shit, these people are on a mission”. And I think that is something that Ben noticed straight away when he walked in here.

To be honest, all the colleagues we have met as we have created the Ineos Britannia team out of motor racing folk and the experienced America’s Cup professionals, they want the same as we do. They want to work in an environment that allows them to get the outcome they are seeking. They are probably a bit more sued to wearing flip flops and shorts, but no less focused on the task.

How much has Formula 1’s introduction of cost caps on the teams this season and for the next two seasons influenced the decision to get involved in an America’s Cup Challenge?

To explain the cost cap: there is literally an amount of money that we can’t exceed in a given calendar year. [The restrictions] don’t cover the gamut of our team’s activities – but if you think of anything to do basically with the concept of design, manufacture, test, build and operation of the car, then the cap applies to all that stuff.

The cap is set at a level that is a considerable chunk below where this team would traditionally have spent in that field. This season was the first year. You have to demonstrate that what you are doing come under that cap. The cost cap actually reduces by 5 million [dollars] a year for two years after this one – 145, 140, 135 million dollars. That generates us a certain amount of capacity for taking on a project like this.

This team was bigger last year than you can afford with the cost cap this year. And that means that a certain amount of our resources is able to work on this type of project. As the rhythm of the Cup campaign requires it, hopefully it will intermesh adequately with the corresponding demands that happen over in F1 land. So that all the skill we have here can be brought to bear.

What conversations did you have with Martin Fischer when the two of you first met on this project?

At the very beginning of the conversations with Martin - and with every other person whose profession and passion has been to design these fantastic racing yachts - is to emphasise that we hope that we properly understand that being good at racing cars doesn’t mean you are good at making yachts. And that what we wish to do is to learn – from people who are good at doing yachts – the manner in which we can best help.

My opening conversations with Martin were to try to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the previous campaign inside Ben’s team, and the strengths and weaknesses of the campaign that Martin was involved with in Luna Rossa.

To try to work out how we can try to amplify the strengths, mitigate the weaknesses, and to see where there are areas of opportunity. For example, things like the engineering standards we have here which any engineering group can gratefully pick up and fall on like manna from heaven to just say ‘well that’s work we don’t need to do’.

Specifically though, [we talked about] what are the likely key features – [given that] we don’t know the venue yet, we don’t know the timing yet, we don’t know lots of things - but what are the likely key features, [like] what sort of level of force are we going to need to have in terms of manpower, effort, and design loops, iterations, in order to have half a chance.

Martin has been really helpful in trying to guide our thinking on that. Then hopefully we have been useful teammates in terms of doing our part to create an environment where people who have made this their life’s work can come here and say ‘yes we can do good work here. And yes, the engineers you’re putting with us are worth their salt’.